Getting things done in 2017

· 10 minute read

I’ve been using OmniFocus to organize my personal and professional lives for a couple years now, but hadn’t actually read David Allen’s Getting Things Done (referred to as GTD for the remainder of this post) – the eponymous book behind the methodology that OmniFocus and many other apps like it are intended to help facilitate – until this past summer. While I took a lot away from the experience, I found it to be far from a perfect representation1 of how I myself would personally try to sell someone on the merits of such a system. This inspired me to try and sum up the aspects that have specifically resonated with me over the past few years, and how I would pitch them to someone considering adopting something similar for themselves.

This is the essence of how I (lowercase) get things done in 20172. These concepts are universal enough that you shouldn’t need any specific software in order to start incorporating them, if interested.

A “mind like water”

For some time, I made the curious mistake of thinking that the desired outcome of adopting a productivity methodology was purely to become more, well, productive. It wasn’t until I actually read GTD – years later – that I realized I had been missing the point pretty significantly. Increased throughput is certainly a side effect of implementing a trusted and comprehensive system. But more important is preventing your brain from needlessly churning away on tasks that you realistically can’t (or simply don’t need to) act on in that specific moment. For example:

- If you’re subconsciously concerned that you’re going to forget about something that you need to do the following Tuesday, you might not be fully present in order to enjoy your weekend.

- If you’re at the office but are being reminded about errands that can only be performed at home each time you look at your to-do list, you’re wasting valuable mental energy.

This is easily avoided. At risk of sounding trite, it should be clear that time truly is our most valuable resource. A system that helps us take care of what we need to only when and where we actually need to (and can) lets us make the most of the time that, as such, we don’t need to spend worrying about whether we’re “being productive” or not.

Out of your head, into the inbox

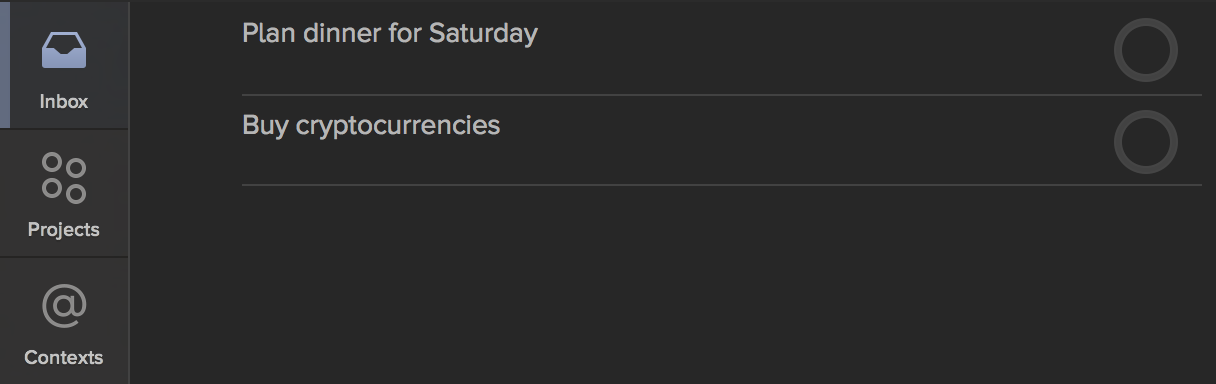

One of the biggest limitations of the simpler to-do lists I’ve used in the past is that they don’t generally make a distinction between tasks that have been thoroughly considered and prioritized, and unorganized thoughts that have simply been thrown into the mix, to be triaged later on. An “inbox” provides exactly this distinction. No random idea is too nascent or scatterbrained to be put into the inbox, and getting something in should be as frictionless and lightweight as possible3.

Inbox entries won’t actually be worked on until you’ve had more time to think about them, augment them with any necessary additional information, and break them down into granular sets of actionable steps (which you should do every couple of days; I try to keep my inbox from growing larger than ten items or so). But merely getting a thought out of your head is intentionally a very different process than fully “entering it into the system,” and to great effect.

Projects you can actually finish

Describing projects in a way that makes them “actionable” is a small change that can have a big impact, regardless of what methodology you choose to employ4. “Exercise more” is a noble goal but not a particularly actionable one. In practice, when would you be able to mark such a project as “completed”?

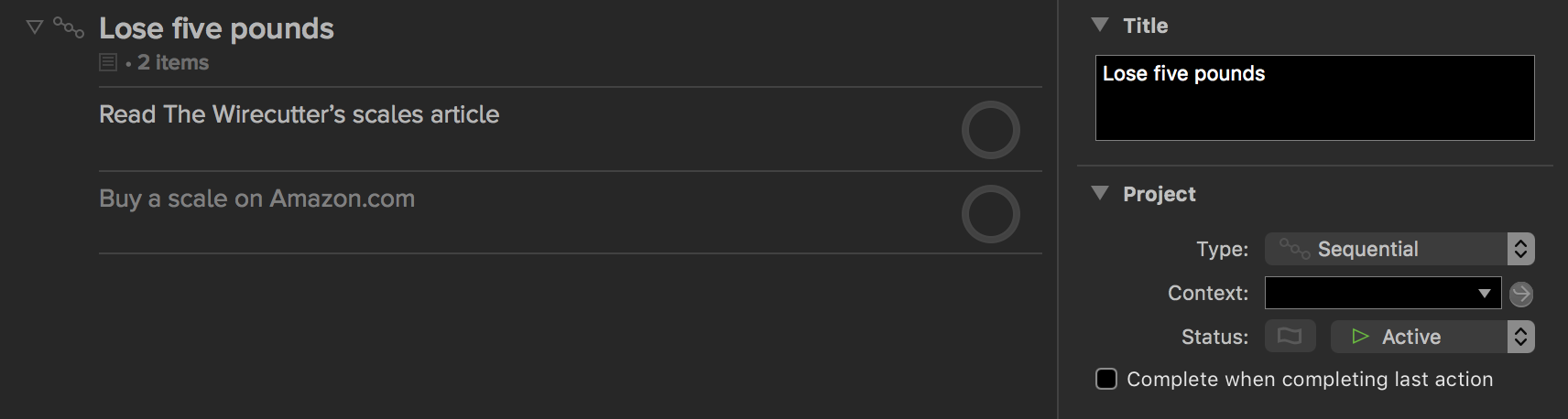

Quantifying that you’d like to e.g. “Lose five pounds” is specific and achievable; a goal that you can actually hold yourself accountable to. One that you can actually remove from your list once you’ve accomplished it, rather than something open-ended and liable to linger in perpetuity.

What’s next?

“Lose five pounds” is a nice and finite name for a project, but how will you actually go about making it happen? If you’re scanning through your to-do list looking for something easy to pick off, in what specific moment is “lose five pounds” ever going to feel particularly accomplishable? GTD would suggest that a project like this be broken down into specific granular actions; a good first few actions for this particular project might be “Read The Wirecutter’s article on digital scales” and “Buy a scale on Amazon.” By reframing the project in this fashion, you’re putting yourself in a position where you can actually make progress towards your goal while sitting at your desk during your lunch break.

Even better, if you can’t proceed with the second task (“Buy a scale”) until you’ve finished the first (”Do the research”), your to-do list should only show you the first. Don’t waste brain-power thinking about work that can’t actually be done yet.

Does breaking projects into actions sound like it’d be time consuming? It can be, but this is work that you’re going to be doing one way or the other: either explicitly, when you enter tasks into the system, or implicitly, when actually trying to work on them. By front-loading the act of outlining these individual steps, you’re only putting the effort in once, and doing so at a time when you’re actually in the right mindset to strategize. This way when you have thirty minutes between meetings and are looking to see what can be accomplished, the only work left is the work itself.

Working contextually

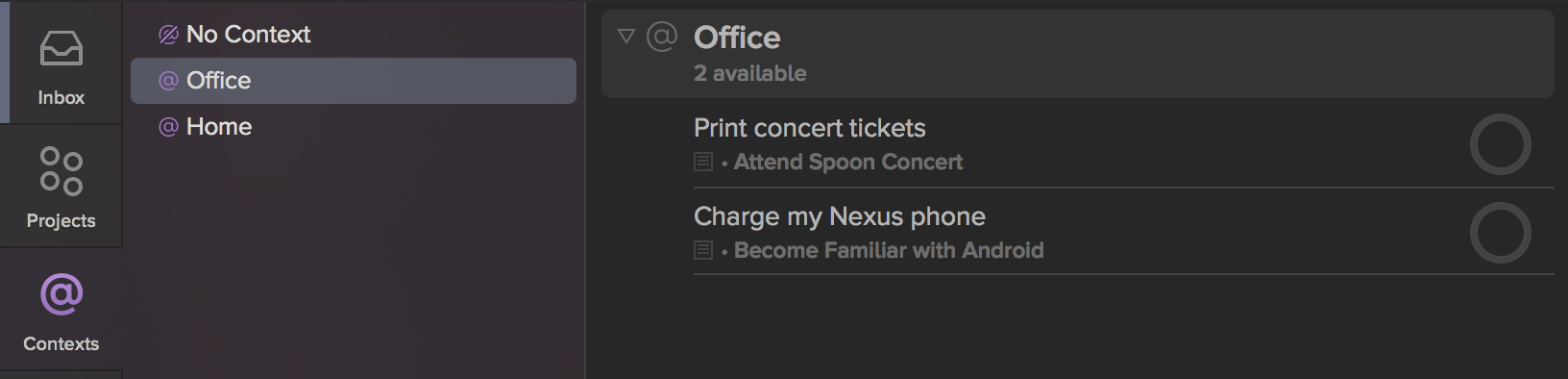

You can’t necessarily perform any task at any time. Tickets for a concert don’t go on sale until Tuesday. Picking up your prescription can only be done while in a certain neighborhood. You might have the right time/energy combination to power through some mindless busy-work but not write a letter of recommendation for a friend.

GTD refers to such constraints as the “context” that a given task can be performed in, but doesn’t prescribe much about what your contexts should actually be. They can be a place, a person who you need to talk to, a combination of time available and current energy level, and so on and so forth. You can make a Calls context if you like getting all of your phone calls out of the way while walking to and from the grocery store, or a Waiting context to easily group tasks that you’re waiting on someone else in order to proceed with, and as such don’t need to consider when proactively looking for something to do.

However you define your own contexts, being able to say “I’m in this context, what can I do?” gives you all of the signal without any of the noise.

Just because it was due doesn’t mean it was done

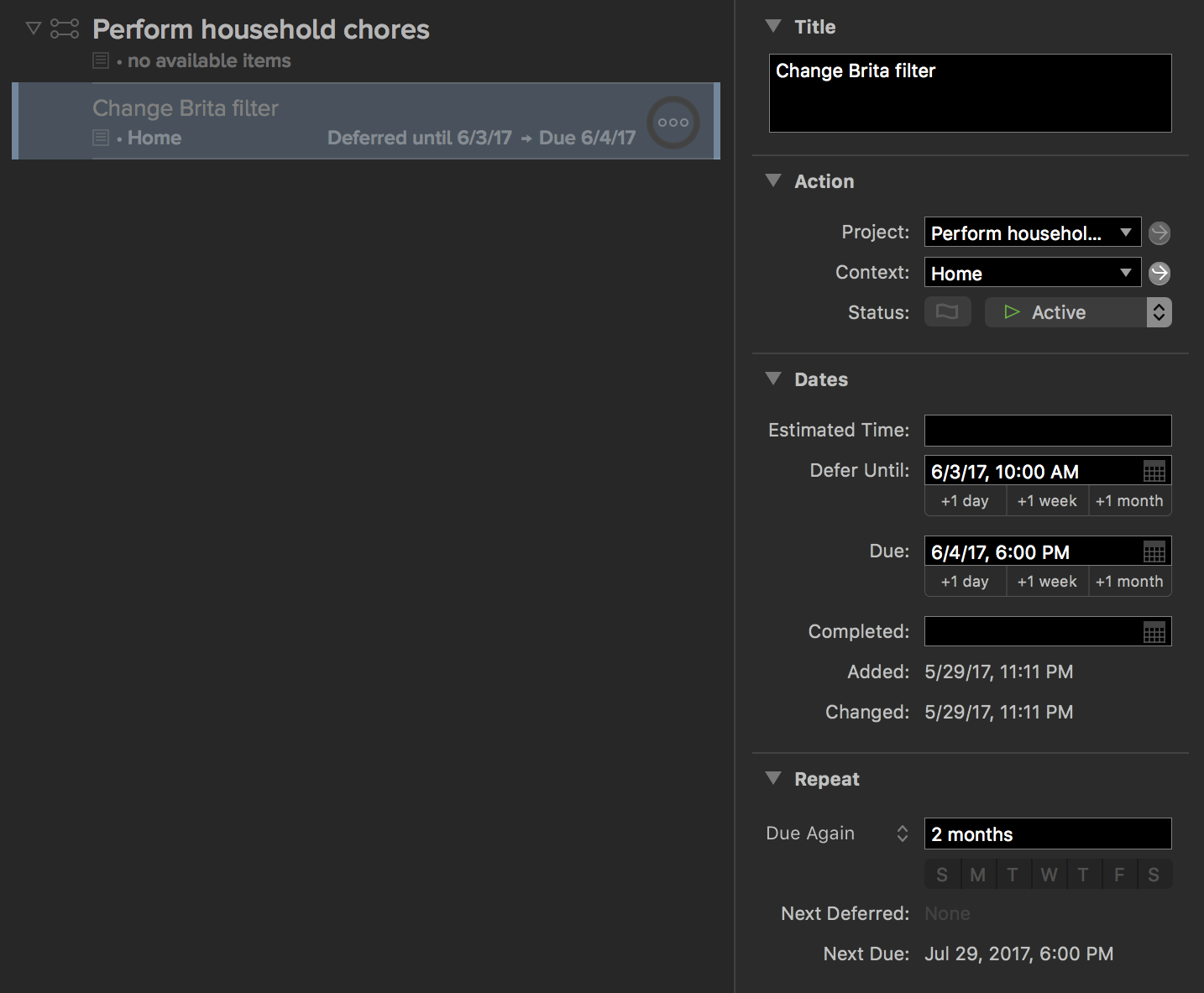

I used to use calendar events to remind me about tasks that needed to be done on a specific date and time. This wasn’t ideal because calendars events are effectively “done” once their start date has passed, whether or not you actually did what you were supposed to. Tasks that are due but haven’t been done yet should be impossible to overlook, while calendar dates in the past are anything but. If you use your calendar like this today, I’d recommend a task list with due date support instead.

When using software that allows you to assign dates to tasks, it might be tempting to do so aspirationally, e.g. “I’d ideally like to accomplish this on Wednesday, so let’s make it ‘due’ then.” I’d strongly advise against this, as it makes it really easy to stop trusting the system and ignore tasks that really do need to be acted on by a certain date and time. I’m not the only one to have reached said conclusion.

Modern task lists like OmniFocus even allow you to get a bit more sophisticated when it comes to recurring tasks. If you’re supposed to perform a household chore every three weeks, but end up slacking off and waiting five weeks before actually doing it, it probably shouldn’t be “due” again one week later. Instead, it should probably be due three weeks from whenever you actually did it the last time. Hard to do with a calendar, but easy to do with software meant expressly to handle such complexities.

Review everything every week

To achieve a “mind like water,” we need to fully trust that everything important is both captured and going to be surfaced when appropriate. To feel comfortable blindly throwing every barely-considered idea into the inbox, we need to know that the overall list won’t grow out of control, and that crucial work won’t be obscured by anything superfluous. Simply reviewing your entire system once per week can address these concerns, and more.

We’ve already touched on how one of GTD’s pillars is compartmentalizing the time spent planning work from the time spent doing it. Setting aside a little bit of time e.g. every Sunday afternoon to get all of your planning done means the rest of your week can simply be spent doing.

Close projects that aren’t applicable anymore. Create a new project that you’re only now realizing the importance of. Check off actions that you completed earlier in the week, but forgot to check off at the time. And so on and so forth. After the review, your whole system will be fully up to date.

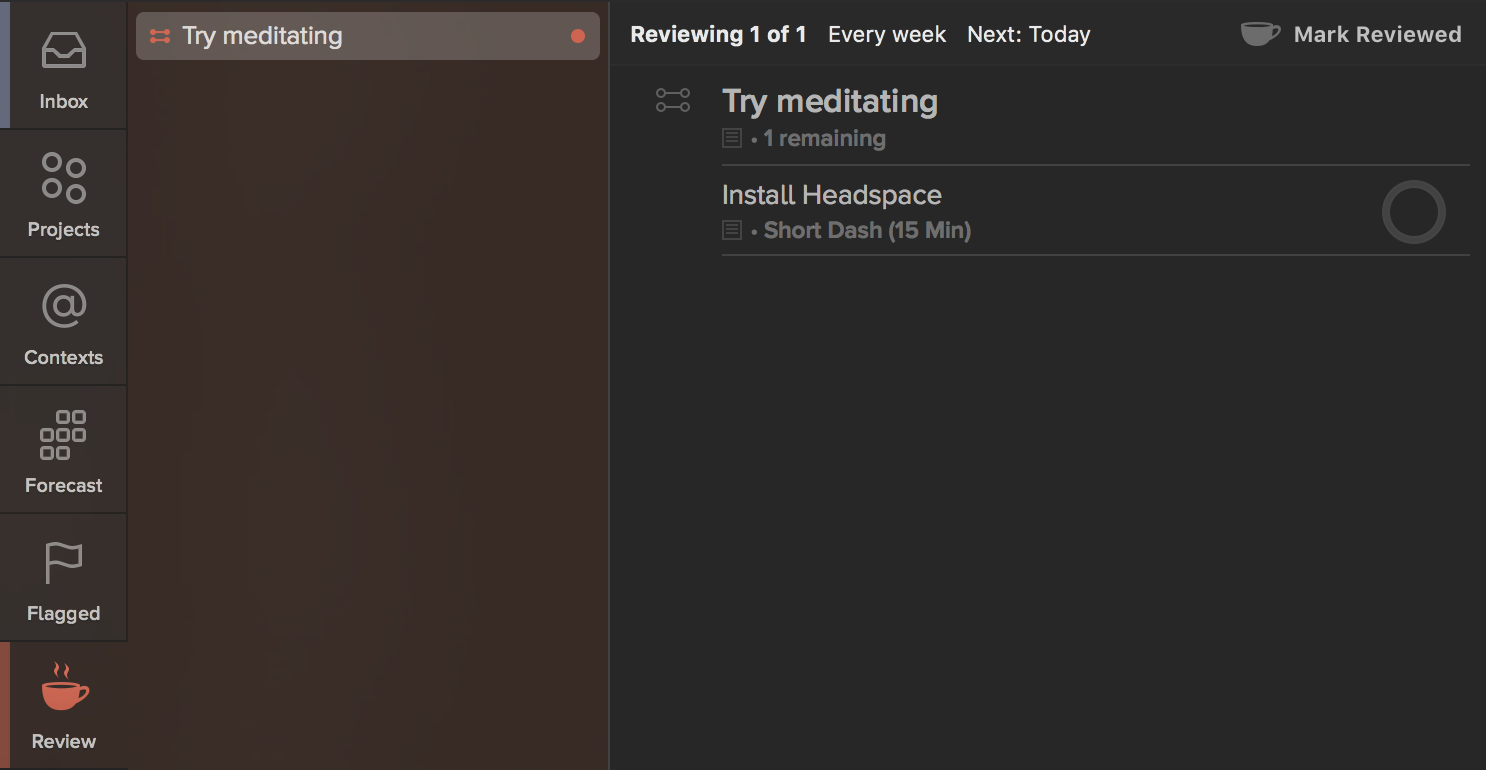

This isn’t as time-consuming as it may sound once you get the hang of it5, but while reviewing can admittedly be somewhat tedious, this is all the more reason to be quick to discard projects that you realistically aren’t going to do anytime soon. If you keep seeing “Try meditating” during your weekly reviews, but know you probably aren’t going to get around to it after all, just remove it. You can always add it back later if your schedule opens up, or a project becomes more important than it previously seemed to be.

Can be done in two minutes? Then do it

It should be painfully clear by this point that a GTD-like methodology requires more commitment than, say, a list written down on a piece of paper. You’re phrasing projects in a way that makes them completable, breaking them down into granular actions, giving them contexts such that you’re only working on them when you actually can, and reviewing them weekly to ensure that nothing’s ever out of date. That‘s quite a few extra steps, and all the more reason to not do all of this in lieu of simply completing something right away, where appropriate.

While converting the stream-of-consciousness brain garbage that we lovingly call an “inbox” into fully-vetted projects and actions, if you come across something that you could realistically finish in just a couple minutes, simply do it and move on. Learn to feel guilty about spending more time organizing what you want to get done rather than actually doing it. Use the full system for projects that’ll actually reap its benefits, and treat anything else like you would a bullet on a non-hierarchical piece of paper.

Continuing what I learned while writing my last post, productivity is incredibly hard to write or talk about given how uniquely we all respond to different types of motivation. Many of my friends and family members are great at keeping their “systems” in their heads, and don’t have a hard time living in the moment while still accomplishing everything they need and want to in their personal and professional lives. For them, incorporating the ideas outlined above would be more trouble than it’s worth. My brain simply doesn’t work that way.

Making a concerted effort to set ambitious goals without allowing them to consume my every waking thought has dramatically improved my well-being and ability to enjoy time spent with loved ones. If you’re at all like me, I’d implore you to try doing the same.

Many thanks to Matt Bischoff for both providing feedback on this post, but also for introducing me to many of these concepts in the first place.

-

GTD focuses a lot on the business world, and despite having been updated somewhat recently, also assumes a fair bit of offline, physical organization (as opposed to exclusively using a software solution like OmniFocus). ↩

-

This should be obvious, but I’m omitting plenty of the actual GTD methodology, and likely not doing justice to some of the parts that I’ve chosen to highlight. If I misattribute some my own opinions to David Allen, it’s unintended and I apologize. ↩

-

OmniFocus in particular makes it incredibly easy to add to the inbox via Siri, a 3D Touch home screen shortcut and a Today widget on iOS, and a global hotkey on OS X. You can even add tasks via email or Amazon Alexa. ↩

-

Here’s a helpful list of verbs to consider when trying to phrase your projects and actions in a productive way. ↩

-

OmniFocus in particular has first-class “review” functionality that allows you to set a weekly review time. It then reminds you when it’s time to review and makes marking individual projects as having been “reviewed” a breeze. ↩