How I learned to read (with regularity, as an adult)

· 6 minute read

Yours truly, in January 2013:

Last year I only read two books. I’m disappointed by that, and my goal this year is to read somewhere closer to ten, alternating between fiction and non-fiction. To hold myself accountable, I will try to write a little about each, starting with this one.

I only ended up reading five books in 2013, but read seven in 2017 and seventeen in 20181. At risk of jinxing it, I think it’s safe to say that – many years later – I’ve finally adopted a real reading habit for the first time as an adult.

Habits are obviously quite personal, and there’s no shortage of advice out there on how to make one out of reading in particular2. Here are the few keys to my own personal success on this front that I hope may prove helpful to you as well.

Committing to a platform

I spent far too long being really indecisive as to whether I should invest in Apple or Amazon:

Sadly, I’m positive that I’d read a lot more if I wasn’t paralyzed by indecision over iBooks vs. Kindle lock-in.

— Bryan Irace (@irace) July 14, 2015

iBooks or Kindle? Lock-in indecision usually results in my just not buying anything.

— Bryan Irace (@irace) February 1, 2016

I eventually committed to Amazon due to Goodreads, local library rentals, and e-ink Kindle devices (more on all of these later). Most important was to simply make a decision, however; I think I’d be doing just fine had I chose Apple instead.

I still prefer Apple for programming books because I find the Apple Books software for macOS to be far superior to Kindle’s desktop web experience, but these are a small percentage of the books that I read overall. I’ve been very happy with Kindle as my default for everything else.

Keeping a streak

If you’re the type of person who finds streaks to be motivational, keeping track of a streak is an easy way to make sure that you’re spending at least a few minutes reading each day. Just five or ten minutes each day is a great place to start; those minutes really do add up, but perhaps more importantly, a streak helps ingrain the habit of dipping into your book during your commute or while waiting in line at the grocery store. Or really, anytime when you might otherwise default to scrolling through Twitter or Instagram.

Allowing myself to take breaks from books

There are some days where I simply don’t want to read a book, but that doesn’t mean I can’t read something else of value. The goal here was to instill a reading habit, not necessarily a book habit.

Maybe I just finished my last book and haven’t decided which my next one will be, or maybe there’s a lot going on in the news that I’d like to catch up on. I use Instapaper to save articles of all different kinds to read at a later date, and on days where I choose to spend at least ten minutes reading these instead of a book, I’m happy to count that against the streak as well.

Using an e-ink Kindle

I resisted getting a dedicated Kindle device until December 2016, primarily because I really don’t mind reading on iOS. I’ve read entire books on iPhones without issue.

I eventually moved to a Kindle as my primary reading device not because I prefer e-ink screens to LCD or OLED, but because I am very bad at avoiding distractions. My Kindle doesn’t have notifications, a web browser, or a Twitter client. I can do nothing but read on it, so read without interruption I do.

Modern Kindles also have the benefit of being quite light and small. I expected to only bring mine along when carrying a bag, but it fits pretty easily in many of my jacket pockets. As such, I’ve carried it far more often than I would’ve originally guessed.

Reading wherever, whenever

Despite having really grown to like my Kindle, it’s only with me a fraction of the time compared to my iPhone. Like with cameras, the best book is the one that’s with you. Kindle sync means that your book is always with you as long as your phone is, even if your primary reading device is not. And as mentioned, I’m definitely not above reading books on my phone.

There are plenty of times where I most certainly do not want to carry anything more than my phone – specifically in the summer – but this doesn’t mean that there can’t still be any number of planned or unplanned reading opportunities along the way.

Drowning out the noise

In the spirit of reading wherever and whenever, it’s often helpful to have something to help you drown out the background noise of your neighborhood coffee shop, or the New York City subway. I’ve been using Brain.fm almost exclusively for the past year but have also used Noizio a lot in the past. They’re both really good at what they do.

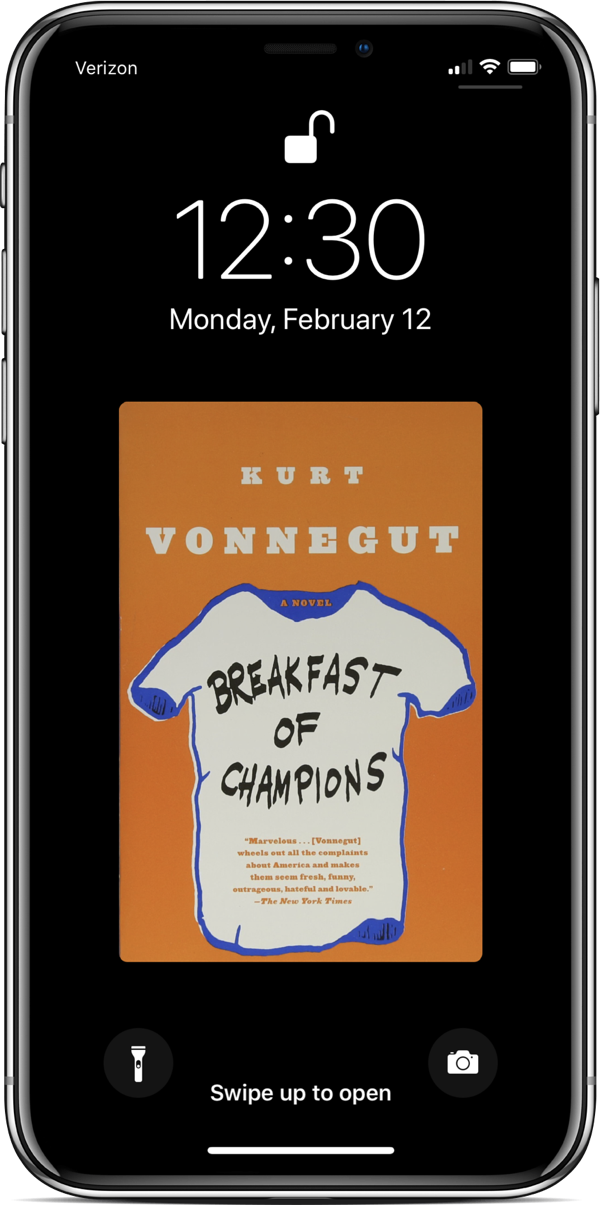

Putting a book cover on my lock screen

Whenever I start a new book, I put the book’s cover on my iPhone lock screen3. It’s not exactly subtle, but I benefit from the constant reminder that I could be reading my book whenever I’m tempted to use my phone for something less beneficial.

If you’d like to make your own lock screen wallpaper, here’s the Sketch template that I use.

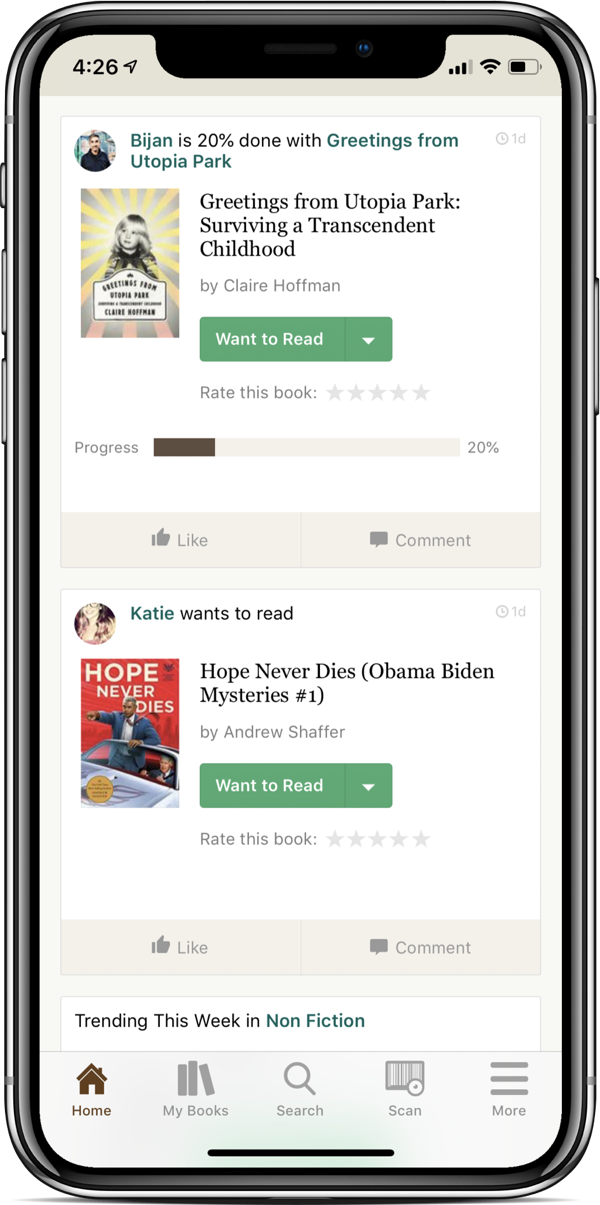

Using Goodreads

Goodreads is a social network for keeping track of what you and your friends are reading and want to read in the future. It’s owned by Amazon, and as such is able to automatically track any books that you’ve read using Kindle apps or devices.

While the website and iOS app could both use a bit of user interface love, I’ve found it to be a huge help in keeping a reading habit by providing:

- A steady influx of new book suggestions, specifically from those who share your tastes

- Encouragement in the form of annual challenges

- Guilt, if you’ve lapsed a bit yet see all of the books that your friends keep finishing

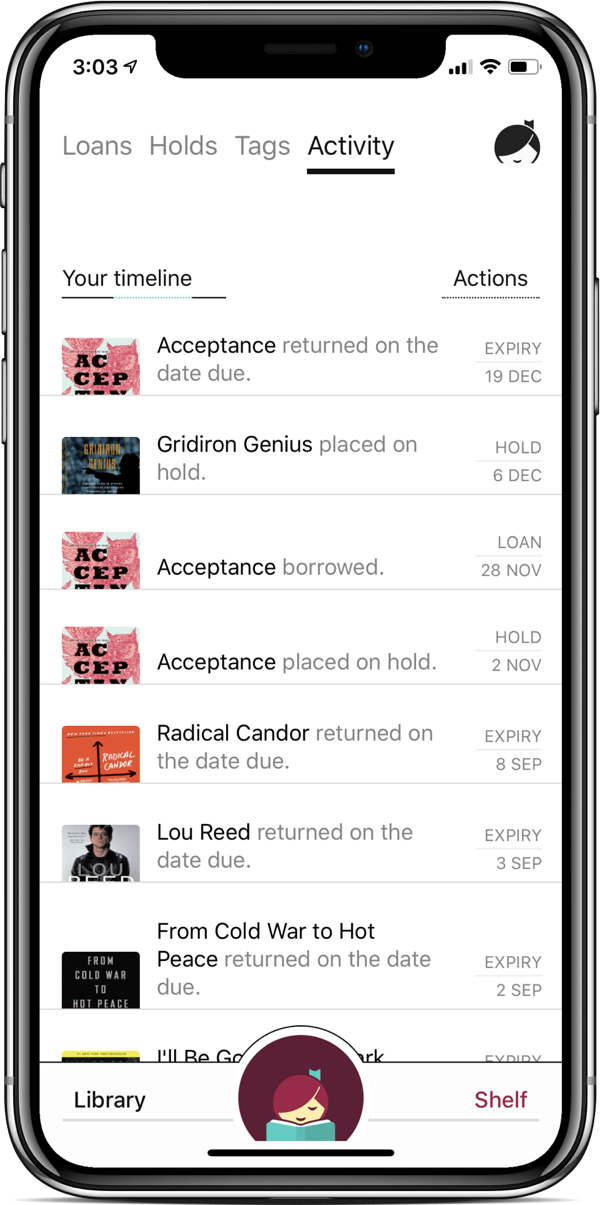

Renting from the library

Did you know that not only can you borrow physical books for free from your local library, but ebooks as well? More surprising, perhaps: Libby, the iOS app used to do so, is actually quite nice.

The selection isn’t perfect, but I’ve been able to find a lot of books on my reading lists at either the New York or Brooklyn Public Libraries4. You may need to wait a few weeks for popular books to become available, but you can put them on hold such that they’re automatically rented once they are. Once rented, you can keep the book for up to 21 days (which I’ve found can serve as a helpful forcing function to make sure you’re moving through it with haste).

These are just a few tactics, but they’ve worked well for me over the past year and I expect will continue in years to come. I still think there’s room for improvement5, but the first step to improving a habit is to have said habit in the first place. As of 2018, I can finally say that I do.

-

I didn’t really keep track from 2014 through 2016. Day One and Goodreads indicate that I read at least three in 2014, at least three in 2015, and at least two in 2016. Nothing to brag about. ↩

-

A couple of favorites: this one from Rick Webb (my former Tumblr colleague and a far more prolific reader than I am ever likely to be), and this one from Paul Stamatiou. ↩

-

I wish I could take credit for this, but I got the idea from Twitter at some point and can’t find the source for the life of me. Apologies! ↩

-

Your mileage may vary depending on your local library, of course. ↩

-

Specifically, retaining and utilizing information gleaned from non-fiction books. ↩